#17: Three stories

Hey!

Today I'm trying something different. I wrote three brief stories — all of them exploring an aspect of the world I'm fascinated by lately.

I hope you'll find them illuminating too.

Here we go.

I. Should you be afraid of the dark?

As long as I can remember, I had a certain fascination with Stephen King.

Which is unfortunate because as we've established many times, horror is not really my genre.

The first King book I ever read — and for a long time the only one — was The Shining. I remember buying it before a long train ride. It was in 2017, and I was only a few months out of medical school. The utter exhaustion caused by my training to be a respectable physician just started to lift, and I could finally entertain the idea of reading again. So on a whim, I bought the book, a sandwich, and a bottle of water, and tucked myself away in the corner of a train coach that was several decades older than me.

At least. (It had seen better times too.)

As the train wound its way toward the North, the sandwich went untouched. Most of the water as well. I was simply too busy being sucked deeper and deeper into the madness of the Overlook Hotel.

I finished the entire book during that trip, and by the end, I was properly terrified. Here's what I wrote at the time in my Goodreads review:

I don't think I can stay at a storied hotel up in the mountains ever again. This book is good. It's clever in its prose, terrifying in its story, and most interesting in its characters. Definitely worth a read.

Then I didn't touch another Stephen King book for six years.

(I didn't go to old hotels in the mountains either, if you're wondering. And I still don't.)

Occasionally, I was bummed about this in the intervening years. I wished King would write stories that didn't include horrifying sewer clowns, vengeful cars, and rabid dogs. I loved his prose, his pacing, his stock-like, yet endearing characters. In more ways than not, King was a perfect writer for me.

But unfortunately, he also left me with nightmares lasting almost a week after I finished The Shining.

So I put King back on the metaphorical shelf, and things stayed that way until 2023.

That year, I was looking for some good books on the craft of writing, and the internet kept recommending yet another Stephen King joint — his only non-fiction piece —, On Writing. Picking it up, I expected a handbook, but what I found instead was what I'd been craving all along.

On Writing is divided into two parts: the second is the guidebook for writers, but the first one is a sort of autobiography. King wrote it as a series of vignettes, strung together loosely to try and puzzle out why he became the writer he is. It reads exactly like one of his novels — only without the horror parts.

But the biographical chapters turned out to be only the second-best thing On Writing had for me.

In the second part of the book, King goes into explaining how he approaches certain challenges of being a writer, and he illustrates each lesson with examples taken from his own work. He mentions maybe two dozen books he's written, and halfway through, it dawned on me:

Stephen King is not a horror writer.

I mean, he does write horror novels and we all associate him with that particular genre, but in reality, he also writes science-fiction thrillers (The Dead Zone), contemporary fantasy (The Dark Tower series), realistic literature (Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption), and crime fiction (the Mr. Mercedes trilogy).

Looking at it now, I'm not even sure horror is his main genre.

By the time I finished On Writing, I had a handful of King novels I never heard of and what seemed safe enough for a scaredy cat like me. But even then — like all good Stephen King books — On Writing still had a final twist left.

The back matter of the book is filled with a few essays and interview transcripts. One of the latter is about a small podium talk King did with his son, Joe Hill, who's also an author. They are taking turns pulling audience questions from a hat. Mid-way through, King picks the following one:

Joe, what is the most messed-up thing your dad did to you as a child?

And Hill gives a really surprising answer to the audience and his dad:

I know. It’s hard to decide. The thing is, I’ve thought about this a lot because there’s this old Jay Leno joke, right? And it goes, Stephen King asked the kids, do you want to hear a bedtime story? The kids go, “No!” But the thing is, it was never really like that, you know? I mean, we always loved bedtime stories. It was the best part of the day. And I sometimes think that it’s a basic misunderstanding of my dad’s work that he sells fear. Politicians sell fear. I’ve always thought that my dad’s stories sold bravery, that they essentially were making an argument that, yeah, things might get really bad. But if you have some faith and a sense of humor, and if you’re loyal to your loved ones, sometimes you can kick the darkness until it bleeds daylight.

Stephen King is not out there to teach you fear.

He's out there to show you that bravery, humor, and loyalty can carry you through fear.

You don't have to be afraid of the dark. The dark has to be afraid of you.

I found Joe Hill's reinterpretation beautiful, and it was as if a light had been suddenly switched on inside me. After On Writing, I picked up a copy of The Dead Zone (a non-horror entry, four stars, loved it) and one of King's most famous horror novels I wanted to read for ages, but didn't dare, 'Salem's Lot. It did give me chills at times, but nothing like the deep fear The Shining instilled.

(Three stars, by the way. It was good, but not as good as The Dead Zone.)

So, why am I telling you all this?

First, because Stephen King's books are amazing, and if you like good writing, you might want to try them. I can personally vouch for The Dead Zone — that's my current favorite.

Also, quick aside: there's this really good podcast — Just King Things — where two very smart (and funny) fans read every novel King ever wrote in publication order, then they talk about them in detail. I recommend them.

Okay, back to the topic at hand.

The real reason I was thinking about King so much is narrative.

Specifically, the narrative I tell myself about myself and the world around me. Lately, I think about it a lot because as I get older, I'm starting to realize that it's possibly the most powerful thing shaping someone's life. You know... intersubjective realities and whatnot.

Nothing changed in Stephen King's books. The Shining is still The Shining, complete with a malevolent hotel, a frightful father, moving hedge animals, and an axe splintering wood ever so scarily. But I bet if I read it today, it wouldn't scare me half as much.

Because inside, I decided not to see the horrifying sewer clown, the vengeful car, or the rabid dog, but the humor, loyalty, and bravery.

Now I tell myself to kick the darkness until it bleeds daylight. And that changed everything.

It makes me wonder: what other narrative of mine could change to open up whole new ways?

And you? What do you tell yourself... about yourself?

**

One down, two to go. Let's do something lighter, what do you think?

**

II. English is just badly pronounced French

If you want a surefire way to rile up a British nationalist, just mention the French.

For example, check out this gentleman — a disillusioned former Leave voter — when a reporter asks him whether he regrets voting for Brexit:

Reporter: Do you say you regret voting to leave?

Gentleman in the (German) Adidas jacket: Partially, yeah. A little bit. But there are bits that... I.. I can't get past France and Germany. Don't like them. I never have done.

You could probably sneer and say: "Oh well, that's nationalism for you. Nationalists are xenophobes who hate everyone."

But you'd be wrong.

The same gentleman in the same interview speaks quite fondly about their mixed-nationality neighborhood and especially the delightful Romanian family living next door. He just really can't stand the French and the Germans — specifically.

He's also not alone.

Redfield & Wilton Strategies — a pollster based in London — has been tracking British sentiment toward the French since November 2021. Their latest numbers show that as of July 2023, 15% of Britons still hold an "unfavourable" view of France.

I wonder whether those people know just how much French they are speaking every day.

Yes, French.

Let's wind back the clock a thousand years.

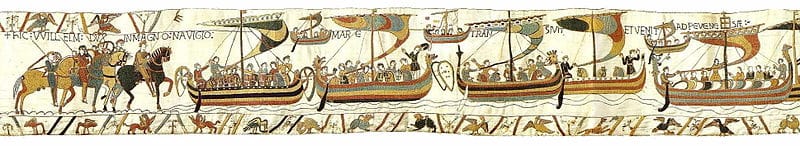

It's 911, and the reigning French king, Charles the Simple, allows a group of ferocious Vikings to settle in Normandy. He doesn't do this out of the kindness of his heart, but because the same Vikings had been burning and looting West Francia for the past three decades, and in their last raid, they even tried to sack the city of Chartres.

Although the Vikings were summarily defeated below the city walls, the king — and his clergy — thought it was better to grab the opportunity now and turn their enemy into an ally. So Charles gives the city of Rouen and the surrounding lands to the Vikings and makes their leader, Rollo, the first Duke of Normandy. In exchange, the Vikings convert to Christianity and pledge fealty to the French king.

And thus, the Normans were born.

Almost a hundred years later, Normandy is a successful territory of France, and the Norman nobility is busy embedding itself into Europe through marriage. As part of that effort, the reigning duke — Richard II — marries his daughter, Emma of Normandy to the English king, Æthelred the Unready.

By the way, can we take a second and appreciate how downright hurtful these noble nicknames are? I mean, hilarious, sure, but also... not nice?

And if you think that maybe Æthelred at least deserved it or something, you'd be wrong. As it turns out, it was just good old-fashioned schoolyard name-calling:

[Æthelred's] epithet comes from the Old English word unræd meaning "poorly advised"; it is a pun on his name, which means "well advised".

Jesus. Well, at least he wasn't called that to his face:

Because the nickname was first recorded in the 1180s, more than 150 years after Æthelred's death, it is doubtful that it carries any implications as to the reputation of the king in the eyes of his contemporaries or near contemporaries.)

Anyway, back to the story:

Æthelred marries Emma, and they have a son, Edward. Later, he'll earn a much better nickname than his father — Edward the Confessor —, and after a bit of exile in Normandy, he ascends to the English throne in 1042. He does this with the heavy support of the Norman side of his family, so Normandy becomes pretty involved in the affairs of England.

Edward rules for twenty or so years, then dies without an apparent heir. Which throws the English court into chaos, but as we've learned from Littlefinger, "chaos is a ladder."

And by that time, Edward's Norman second cousin once removed, William the Bastard became really good at climbing ladders.

He assembles a rather formidable fleet and army and sails across the English Channel, landing on the Southeastern shores of the country. He swiftly erects a wooden castle and starts to pillage the surrounding lands. Lands that mostly belong to Harold Godwinson — the Earl of Wessex and the Englishman whom the Anglo-Saxons have already crowned king.

William's strategy is a real asshole move, but it's a brilliant one too.

Harold is occupied up North with another contender for the crown, and while he's doing well there, he has to maintain a military presence to stay on top. So if he wants to come down to the South to deal with William, he has to divide his forces.

Win for the Bastard.

If he doesn't and stays up North, William can cut him off from his lands and supplies, which in turn bolster the Norman army.

Also a win for the Bastard.

Some people are just better at climbing ladders.

Backed into a corner, Harold chooses to be bold. He takes a part of his army and rides south to meet William in battle at a town called Hastings, where — after a horrifying day of combat — he loses both the battle and his life.

This happens on the 14th of October, 1066.

Almost exactly two months later, William — the Conqueror — is crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey.

Although William's rise to the throne is certainly interesting, what he did after becoming king is why we are talking about all of this in the first place.

To solidify his hold on the new country, he almost completely replaced the English nobility with Normans. Normans, who were loyal only to him, and who didn't speak a lick of Old English. So French became the language of the ruling class and stayed that way for more than a hundred years.

And this is the reason why almost 30% of modern English words are actually French, and why today's English speakers don't have to contend with complicated sentence structures and gendered words. And this is why a few cheeky French like to say that:

The English language doesn't exist. It's all just badly pronounced French.

If the quick story above tickled your interest, I wholeheartedly recommend watching this YouTube video by RobWords.

Rob's essay was where I first learned of English's French connection, and he goes into a lot more detail than I did. Plus, he shares loads of fantastic linguistic tidbits along the way, like how English still displays the fossils of the Norman social structure with its word choices, or why some people still say "an historic" instead of "a historic."

It's a great video, I really do recommend it.

**

Two down, last one to go. This one is for the artist in you.

**

III. The Fat Belly every master has to go through

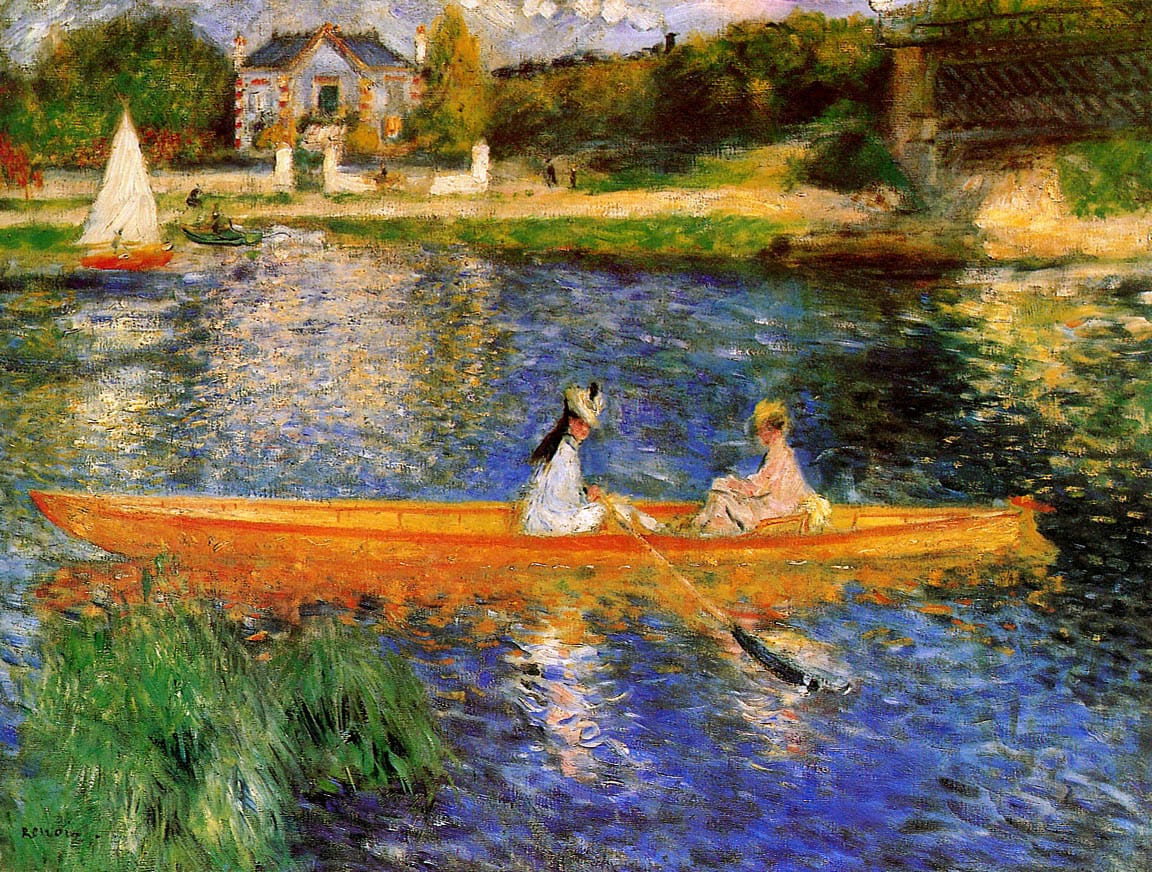

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was a master of color.

Just take a look at his 1875 piece titled The Skiff (La Yole) and you can see for yourself:

Do you want to know something really cool?

He made this with only eight paints — and one of them was white.

Contrast this with the 50+ bottles of pigment I use to paint my little plastic toy soldiers:

Renoir painted one of the most famous Impressionist paintings with eight colors — I painted a goblin's nose with five. Which is A) funny, and B) makes it clear that Renoir could create a much better piece with much fewer tools than I can.

One answer to this would be to point out that Renoir is one of the best painters who ever lived, while I'm a literal nobody. Which is fair. But I think there is a more general — and exciting — idea at play here.

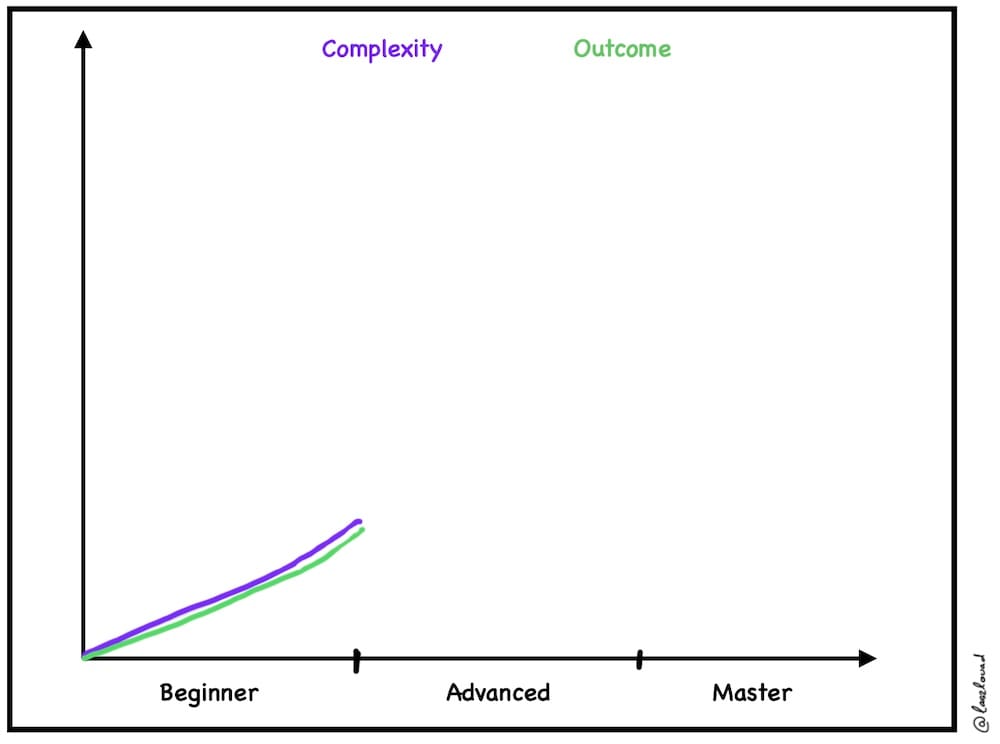

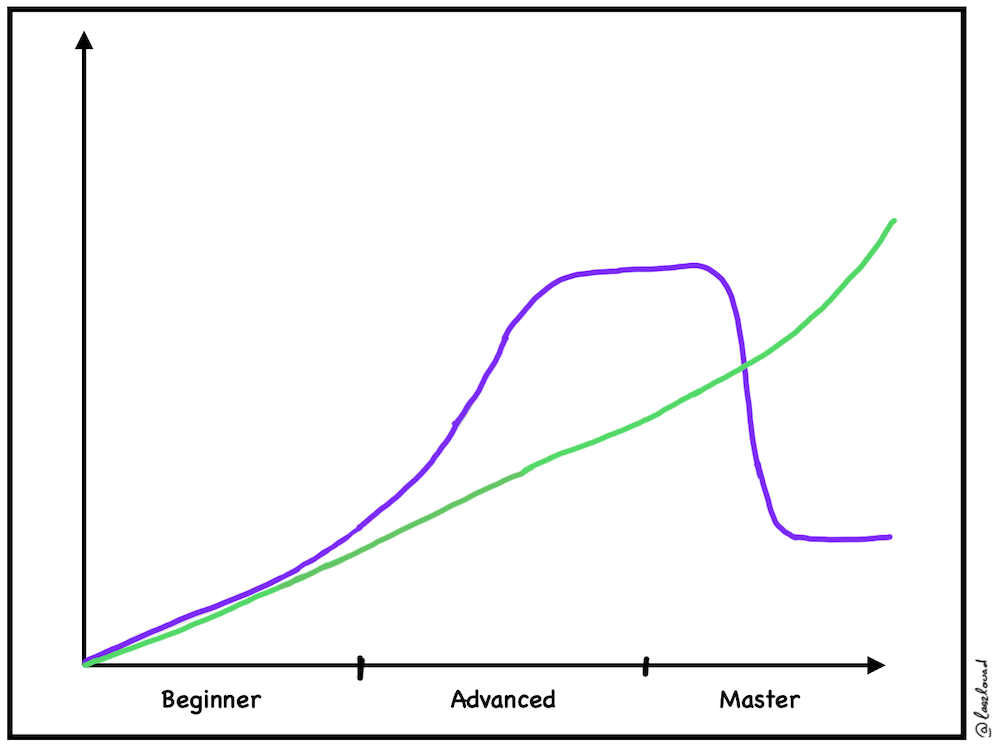

In my head, I call it the Outcome/Complexity curve.

When you start out learning a new skill, the complexity of your tools and skills hovers around zero. It's easy to draw a goofy-looking stick figure, make a computer print "Hello World", or assemble a sandwich. You're not doing anything amazing, but you're also not really breaking a sweat.

You're here:

In this beginner phase, complexity and outcome move in lockstep. You apply a little more effort, and you get a bit better results, but everything remains pretty chill.

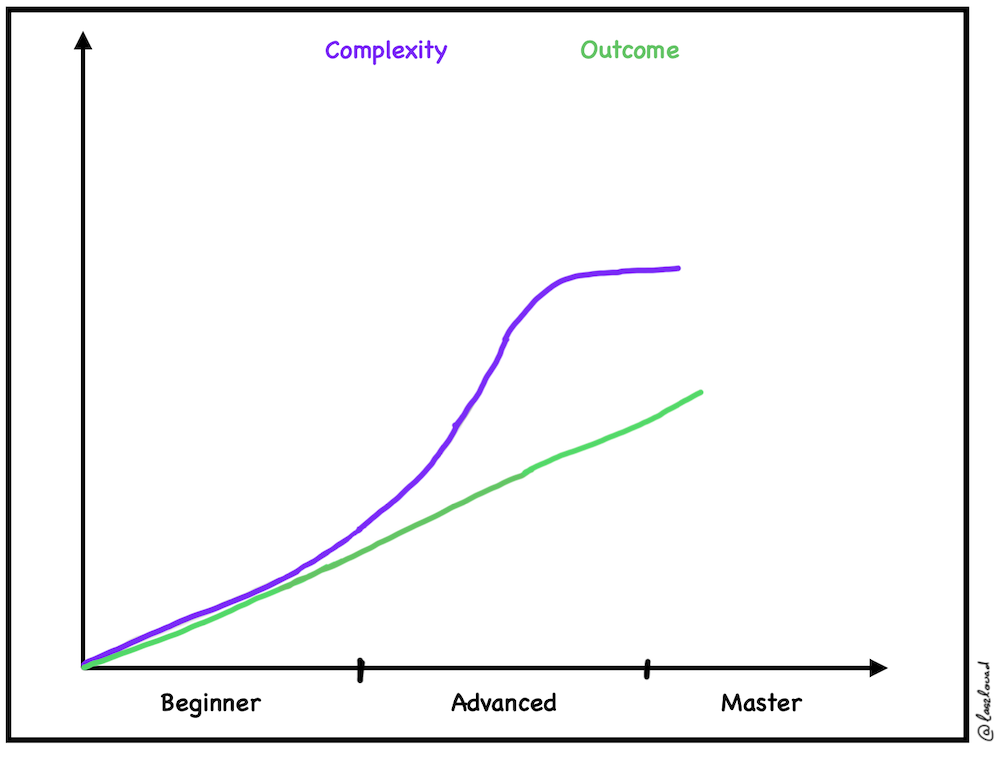

Then, as you get more and more into your new thing, at a certain point you realize how much you don't know. You find out there’s a whole world of tools and techniques you could use to achieve dramatically better results.

You learn of drawing boxes in 3D space to break down complex anatomies into simple shapes. You enroll in Harvard's CS50 course and get deep into the basics of computer science. You buy a really good culinary science book and start constructing and deconstructing flavor profiles.

At this stage, you massively hike up the complexity you're trying to manage.

Usually, this is also the time when you buy a ton of stuff, trying to convince both yourself and anyone who listens that these new shiny things will make you a better artist/programmer/chef, etc. (Pour one out for our ever-patient and supportive spouses and partners.)

The complexity line goes up:

But what about the outcome?

Well, it increases, but a bit differently.

Don't get me wrong, your drawings are definitely getting better. You share a few on Instagram and the likes and comments pour in. Some of your friends even ask if you sell prints.

You write a simple program to take care of the tedious monthly budgeting for you. Sure, the UI is sparse, and the code sometimes breaks on weird edge cases, but more often than not it works and saves you a ton of time. You deploy it to a website and a few dozen people download it. One of them even sends you ten dollars to the tip jar you linked.

You invite your friends over to dinner once every month to show off the new dishes you dream up after work. Every time you do this, they tease you to quit your job already and open up a sandwich shop.

You start to like your outcomes but also begin to chafe against the time and resources you need to spend to achieve them. Your complexity increases exponentially, while your outcomes follow only linearly:

Right about here, things tend to diverge.

Some of us will decide that our thing — be it drawing, programming, sandwiches, or something else entirely — isn't worth this much effort. We scale back your hobby to a level of complexity vs. outcome we can comfortably manage and stay there. Probably for the rest of our very sane and very happy lives.

Then there is the other group.

The maniacs who say fuck it — in for a penny, in for a pound.

These people will start to keep pushing the complexity curve, but now with a very specific question in mind:

What are the things I must learn to have the results I want?

If you're part of this second group, you've already seen all you could learn and realized that a lifetime wouldn't be enough to do it. You also recognize that you only need some of this gargantuan knowledge base to bring your vision to life. So you zero in on those missing skills, and ignore the rest.

This approach, slowly, but surely flattens out the complexity curve, while the quality of the results continues to rise:

And then, at the plateau, you switch questions:

What can I eliminate, but still keep the level of quality?

I think this question marks the first step you take into true mastery.

This is when you start to get rid of all the unnecessary paints and hone in on your eight bottles. This is when you drop the myriad of programming frameworks and define the few developer tools you actually depend on. This is when you sell the two kitchen's worth of equipment, but buy a really expensive grindstone for your best chef's knife.

You relentlessly push complexity down, while your outcome — somewhat counterintuitively — will continue to rise, and even accelerate.

This is when you invert the graph and get to paint The Skiff:

You probably heard the phrase — or even said it yourself — that professionals make whatever they do look easy. (Just watch Gordon Ramsay fillet a salmon.) Only when you try to emulate them do you realize how hard what they're doing really is.

I think the Outcome/Complexity curve explains why that is.

True masters know their craft well enough to know which eight bottles of paint they need out of the thousands. And they also know how to wield those eight bottles.

So, what's the moral of the story?

The first time I articulated this particular idea, it gave me two handholds for practicing art:

One: Complexity of outcome doesn't necessarily mean complexity of process.

I think this is a powerful realization. I don't get discouraged anymore when I see something that looks ridiculously intricate and hard. Instead, I get excited, because I know that there is some relatively simple process of how the artist achieves the outcome.

Yes, it almost certainly took them hundreds and hundreds of hours to figure it out, but given enough time and deliberate practice, I can find the same “simple” process and replicate what they are doing.

Two: There is no skipping the Fat Belly of the curve.

I cannot hack myself into the master territory without going through the complexity gauntlet in the middle. It's not only okay to buy 50+ bottles of paint while I'm figuring out what will be the eight I really need, but necessary. I can only pare down and polish my process if I let myself go wide and learn what is there in the first place.

When I started out running D&D games for my friends, I regularly spent 9+ hours for every 3-hour session. When we finished our big campaign last year, I prepped 1-1.5 hours per session on average. And I think if you'd ask my friends, they would say those later games were much better, much more intricate than the ones I spent 9 hours on.

So now that I'm in the Fat Belly of my painting journey, I happily spend 30-50 hours on a single figure, because I know this is only temporary. As I get better, the time and the complexity will go down, and eventually, I'll get to invert the graph.

Anyway, I guess all I'm trying to say is that there are magical things we humans can do — but we are never magic. If you want to learn something, you can.

And also, go to a Renoir exhibit.

That dude was fire.

And that's it. Three stories. I hope you could take something away from them.

Until next time,

--

Laszlo

P.S.(A.) Hi! Editor Laszlo here with a quick heads-up for you, lovely people of the newsletter.

Extremely Unannoying started out with the intention to be a bi-weekly newsletter. My goal was to get a fresh edition in your hands every other Tuesday. But almost 1.5 years later, I have to realize that this schedule is a bit too much for me.

I'm fortunate enough to have free time I can dedicate to art projects like Extremely Unannoying, but it's a very limited resource, and I have several other endeavors vying for it besides this newsletter.

(Hopefully, I can show you some of them in future issues, but I learned to only make promises when I'm already done with the thing I'm making the promise about.)

So, long story short: Extremely Unannoying will go from an "every other Tuesday" to an "every other sometime" schedule. I still love writing these emails and sending them to you, but they will become a bit more sporadic.

If you don't hear from me for a couple of weeks or months, don't worry. I'm still out there and I'll be back.

Until then, take care, eat a banana, and apply some sunscreen.

They're all good for you I’m told.

Member discussion